History buffs re-enact Battle of Hong Kong on the streets to remind city of home-grown heroes’ defence against Japanese – South China Morning Post

- On December 18, 2016

- 0

Date of Publication: 18 Dec 2016

Link: Re-enacting the role of Hongkongers in the Battle of Hong Kong

History buffs re-enact Battle of Hong Kong on the streets to remind city of home-grown heroes’ defence against Japanese

Too few Hongkongers are aware local volunteer troops helped defend the city against invasion in December 1941, says one of those behind ‘Living Monuments’, a series of battle re-enactments

On December 18, 1941, Hongkonger Algernon “Algy” Ho scoured the skies for enemy planes from an anti-aircraft battery in Chai Wan. Japanese troops had just taken Tsim Sha Tsui and had bombarded the northern shore of Hong Kong Island for days.

Shells soared over the water and exploded into fortifications overlooking the Lei Yue Mun channel near Shau Kei Wan, where Victoria Harbour funnels to its narrowest point. When local troops refused to surrender, the Japanese crossed the harbour, closing in on the colony’s final holdouts.

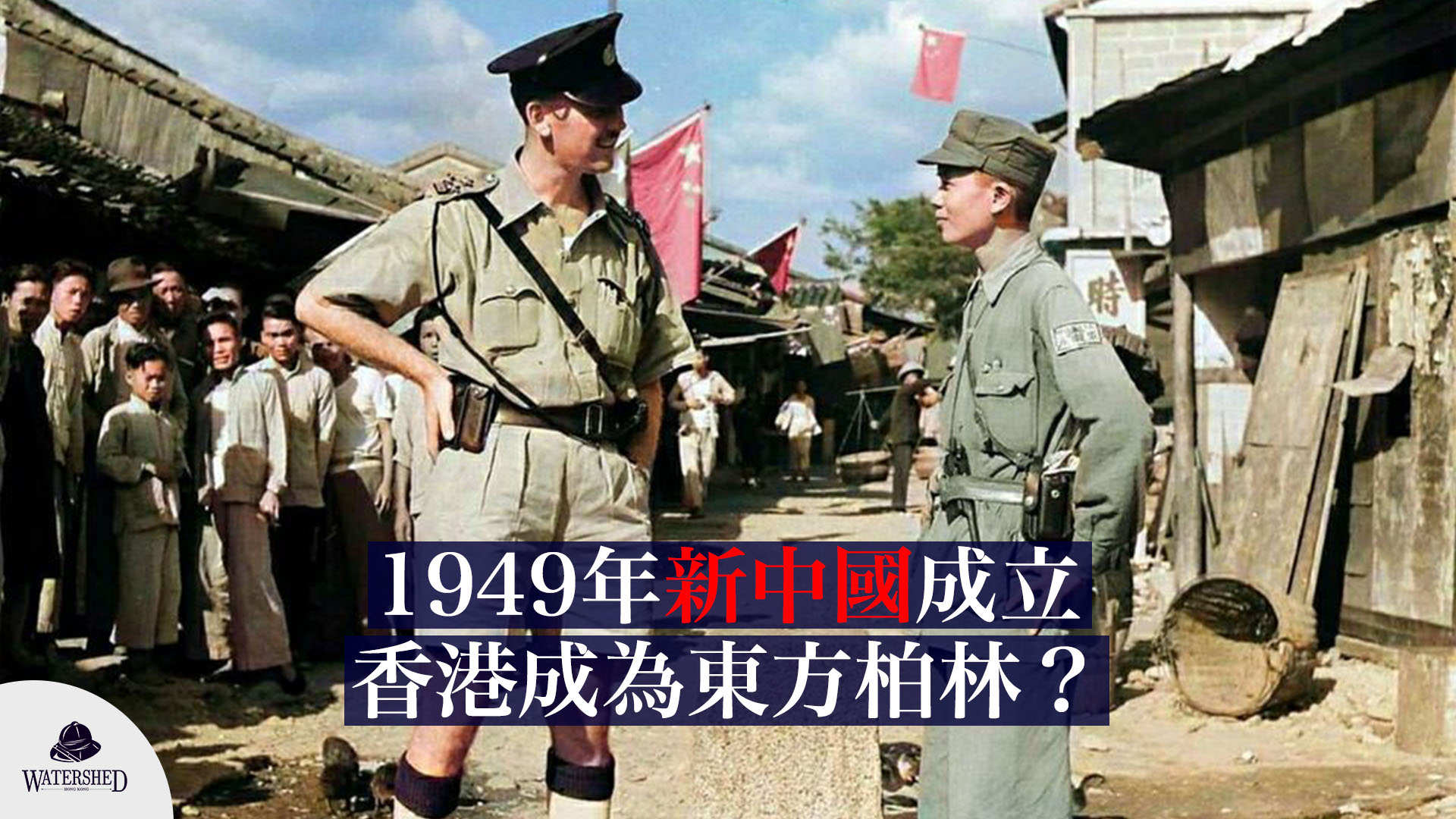

This was the Battle of Hong Kong – the 18-day standoff that ended when the British surrendered the city to Japan on Christmas Day, 1941. Hong Kong went on to endure three years and eight months of Japanese occupation.

Ho didn’t live to receive the bachelor of arts degree he had just earned from University of Hong Kong. Nor was he able to see his younger brother Stanley become the casino king of Macau. He died in action that night, and his fellow gunners who surrendered were executed by the Japanese.

Historical interest group Watershed is commemorating the deaths of these home-grown heroes this month, marking the 75th anniversary of the battle through an event called “Living Monuments”. The initiative is also aimed at raising awareness about an important part of local history that some feel has been neglected and even forgotten by Hongkongers.

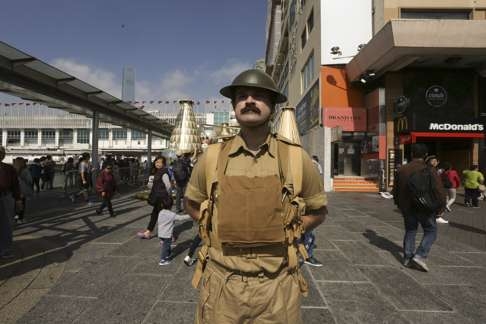

The 30 or so volunteers dress in historically accurate uniforms – made by speciality suppliers in Britain and the United States – and fall into formation in different parts of the city. They will do so again near exit A3 of Wan Chai MTR station from 11am to 2.30pm on Christmas Day. In addition to marching, volunteers are distributing flyers with information on the Battle of Hong Kong.

“People remember the ‘three years and eight months’ of Japanese occupation but always have the illusion that Hong Kong surrendered without a fight,” says Taurus Yip, co-founder of Watershed. “ We [want] to give the public an overview of the war and how [the troops] fought for us and Hong Kong.”

Yip, who came up with idea to bring “Living Monuments” to the streets, is a project assistant in University of Hong Kong’s Technology Transfer Office.Founded in August 2015, his group has held seminars about the battle and organised various activities, such as memorials at Sai Wan Military Cemetery and hiking trips to the second world war forts at Shing Mun Redoubt.

Having studied Japanese and Chinese history at HKU, Yip was inspired to launch this year’s event after learning about a similar project organised last year in Britain to mark the centenary of the 1916 Battle of the Somme.

About 1,400 volunteers, dressed in first world war uniforms, appeared unexpectedly in locations across the country, each representing an individual soldier who was killed. At public squares and railway stations across Britain, they silently handed out information cards to passers-by, each carrying the name of a soldier who had died a century earlier.

Although the efforts of British, Indian and Canadian troops in the Battle of Hong Kong have been relatively well documented and commemorated, Yip says that history has largely forgotten about the hundreds of Hongkongers who fought alongside them.

“Hongkongers do fight for Hong Kong”

Charlie Kwok

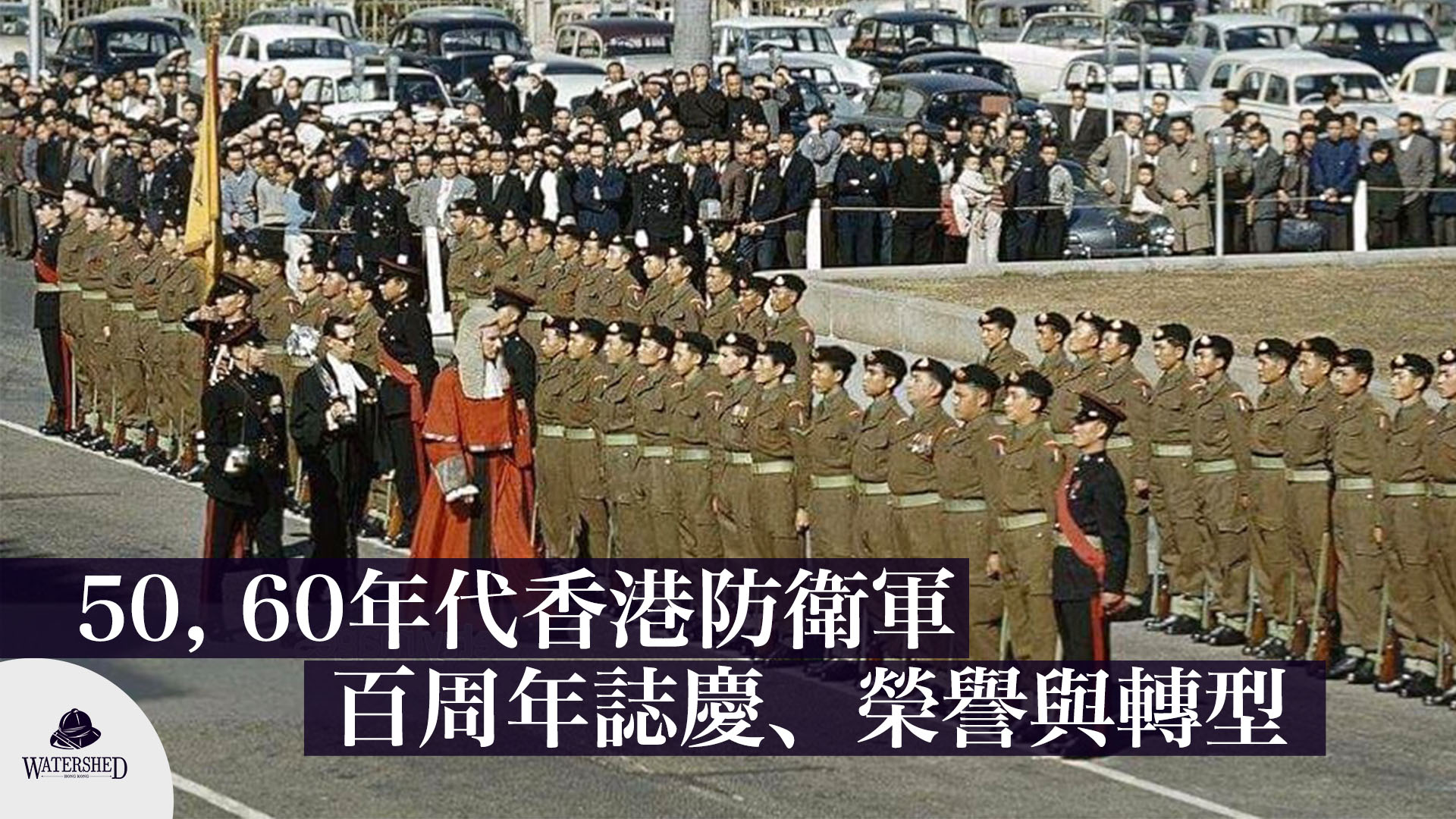

As a result, for the anniversary re-enactment he has chosen to focus on the fallen of the Hong Kong Volunteer Defence Corps, a locally raised auxiliary militia consisting of just under 1,400 volunteers who supported regular units under British Major General Christopher Maltby.

While they only saw light action in the New Territories at the beginning of the Japanese attack, the volunteers were heavily engaged on Hong Kong Island, especially during the key battles at Wong Nai Chung Gap and Stanley, he says.

They fought a series of skirmishes but were unable to forestall Hong Kong’s notorious “Black Christmas” of 1941, when the governor surrendered following a massacre of injured soldiers and medical staff at a field hospital in St Stephen’s College, Stanley. It was the first time a British Crown Colony had surrendered to an invading force.

The volunteers were diverse and consisted of locals with Chinese, British, Portuguese, Eurasian and other backgrounds, Yip says. More than 350 were killed and 148 wounded. Their service was later recognised with the awarding of 19 decorations and 18 mentions in despatches for gallantry and good service.

“The unit not only presents the idea of Hongkongers defending their own home … but also shows that, back in the 1930s and ’40s, Hong Kong was already a culturally diverse community,” he says. “We want to show that history is composed of numerous stories of people. Nowadays, Hongkongers tend to connect everything with political stances.”

Kwong Chi-man, an assistant professor of history at Baptist University who has written extensively on the subject, says the Battle of Hong Kong appears in the local history curriculum. However, the exam-oriented system and limited teaching time prevent in-depth discussion, leading to gaps in students’ understanding about who fought in the battle, and its historical implications.

“The unit not only presents the idea of Hongkongers defending their own home … but also shows that, back in the 1930s and ’40s, Hong Kong was already a culturally diverse community”

Taurus Yip

Also overlooked, Kwong says, are the more than 1,000 Hong Kong Chinese servicemen who served as regular British troops, hundreds of whom survived to rejoin British forces in China and fight against the Japanese in the decisive Burma Campaign.

“Many of these men returned to Hong Kong and continued to serve in the British military or other government services,” Kwong says. “The diversity of Hong Kong’s defenders tells a lot about the cosmopolitan nature of the city, and the significant part played by South Asian communities is a useful counter to the rhetoric about ‘fake refugees’.”

Kwong says that more education could also dispel longstanding myths about Hong Kong’s wartime experience – for example, that Britain turned away reinforcements from Chiang Kai-shek’s Republic of China, or that top military brass disdained local Hongkongers and refused to fight shoulder-to-shoulder with them.

Phillip Doddridge, a 94-year-old veteran of the Battle of Hong Kong and president of the Hong Kong Veterans Association of Canada, told SCMP.com he was heartened to hear of the event.

Doddridge began fighting to defend the colony just 22 days after he arrived in the colony, his first time on foreign soil. At the age of 19, he was thrust into what he calls a world of “hostility, bloodshed, and death” followed by the “brutality, hunger, disease, and often despair” of life in a Japanese prison camp.

“I am glad that there is a movement in Hong Kong to commemorate the battle,” he says. “It is important that those difficult times be forever remembered.”

In the first re-enactment, held on December 11, uniformed volunteers wandered around Tsim Sha Tsui’s Star Ferry pier and the clock tower of the old Kowloon-Canton Railway station. In December 1941, soldiers mustered at this spot before retreating across the harbour to make their last stand on Hong Kong Island.

Most people don’t even know [the city] was involved in the second world war

Charlie Kwok

The contrast between this re-enactment and its forerunners in London and Glasgow is stark. The men’s drill commands barely rise above the din of buskers and traffic, and the sobering sight that moved some to tears in Britain instead elicited curious smiles and requests for photo ops from the sightseers and shoppers assembled before the Harbour City mall.

For re-enactor Charlie Kwok, however, such expressions of interest are encouraging. Although the original “Living Monuments” sought to remind Britons about the human cost of the country’s bloodiest battle, Kwok says too few Hongkongers are even aware of the fact that local troops defended the city against Japanese invasion.

“All I want is to raise their level of interest in Hong Kong history,” says Kwok, a GCSE history teacher at a Hong Kong school. “Most people don’t even know [the city] was involved in the second world war.”Kwok says that the Canadian, British and especially local volunteers who defended Hong Kong are overlooked by the official curriculum he teaches, which instead focuses on the Communist East River Column guerillas.

Having been a part of other re-enactments in Hong Kong and abroad, Kwok admits that his hobby can be expensive. His uniform cost more than HK$3,000 – but he says it makes the re-enactment more meaningful and helps breathe life into history.

After years of dressing up in the accoutrements of the Soviet, US, British and other foreign armies, wearing the uniform of a Hongkonger makes him feel a rare and “special connection” to the historical figures they’re bringing to life, he says.

“[Re-enactments] help you understand modern history and feel like you’re in it,” he says, adding that he hopes the event can help Hongkongers remember what he calls the city’s fighting spirit. “Hongkongers do fight for Hong Kong,” he says.

Watershed’s “Living Monuments” final battle re-enactment will be held near exit A3 of Wan Chai MTR station from 11am to 2.30pm on Christmas Day